Albert J. Parisi

Award Winning Writer and Author

Showcase Essays

Welcome ReaderThe following are a handful of favorite opinion pieces published over the last couple of years that came from the heart, whether as a tribute to one particular writer who was a tremendous influence on my life, or the undying debt we owe to all our veterans, regardless of which war, police action, conflict or skirmish they fought in. In an opinion column, the writer is allowed to paint an extended portrait, work outside the box at times so that the reader can fill in the blanks and come to new terms with any given subject. |

Opinion: As ‘Watchman’ arrives, an ode to a mockingbirdJuly 14, 2015 Last updated: Tuesday, July 14, 2015, 1:21 AMBy Albert J. ParisiTHE RECORD LIKE countless other readers and writers, I'm trying to wrap my head around the fact that the Atticus Finch in Harper Lee's novel "Go Set a Watchman" is far different from the compassionate father and lawyer in the classic "To Kill a Mockingbird." LIKE countless other readers and writers, I'm trying to wrap my head around the fact that the Atticus Finch in Harper Lee's novel "Go Set a Watchman" is far different from the compassionate father and lawyer in the classic "To Kill a Mockingbird." According to early reviews, Atticus is a man in conflict and the cause of disillusionment and consternation for his daughter, Jean Louise. It's now the Fifties, and at age 26 and living in New York, her scrappy tomboy ways, along with her innocence, are behind her. Scout is no more. Atticus laments desegregation and the role of the Supreme Court in its epic Brown v. Board of Education decision and at one point asks his daughter: "Do you want them in our world?" I shall reserve judgment on Atticus until I have the book in hand. It is scheduled for release today. Dare I ask the question: Was the book, an early version of the classic and purportedly discovered by chance in a safe, meant to see the light of day, or is it a bid by the publisher to cash in on its legacy while playing off the hype of recent social strife? For the time being, I will continue to rejoice in "Mockingbird" for its melodic prose and its black-and-white portrait of a small Alabama town in the Thirties that was actually many shades of gray. In a recent broadcast of the "American Masters" series focusing on Lee and her three-year struggle to bring "Mockingbird" to life, one noted author inspired by the novel said part of its appeal was that it touched on both the mysteries and indignities of our youth. Each of us had lessons to learn about those around us and their ability to love and hate, and each of us had "a Boo Radley house in the neighborhood." I believe that each of us has had an encounter with Boo Radley, although we sometimes don't realize it or weigh its impact until much later in life. When my wife, our son and I moved to a small North Jersey town with a country-like setting some 20 years ago, Chris was still young, no more than seven. It was the summer before he was to enter the second grade. Settling in, we'd walk in the cool of a summer night to explore our new surroundings, listen to the croak of wayward frogs at a nearby pond fed by a brook and give thanks for our good fortune. Summer retreat Many of the houses were newer, but there were still a few that had Dutch-settler roots, and still others were a reminder that our town had once been a turn-of-the-century summer retreat for those weary of city life. We took to calling one such home nearby the Boo Radley place. From the house, where rarely a single lamp glowed in its depths, we always felt as if we were being watched, but never was there a sign of life from within. The porch was battered and worn, decades of gray paint flaking and curling. The roof was long in need of repair, and a gravel driveway sloped down a bit of a hill, curving around back by an old carriage house encased in ivy. Across the drive was the crumbling relic of an outbuilding, once a chicken coop, I suspect, caved in by too many brutal winters. A wire fence ran along the perimeter of the property flanking the brook, and the outline of a onetime vegetable garden glistened with moss and misdirected weeds. A flagstone walkway rippled by roots led to a back porch, and a long-handled water pump, once a vibrant cherry red, stood coarsely covered in rust. Long gone now, just off the sidewalk and path leading to the front porch stood a gnarled elm with a knot hole facing the street.  And I'll never forget walking past that gnarled elm and coming to a stop, for we spied something glistening in that knot. I recall Chris reaching in to find a treasure: a new penny or two, and on still other occasions a Crayola crayon, a speckled marble and a chipped, porcelain hare. Was it neighborhood children depositing tokens for others to find, or was it indeed Boo longing to connect with others? And I'll never forget walking past that gnarled elm and coming to a stop, for we spied something glistening in that knot. I recall Chris reaching in to find a treasure: a new penny or two, and on still other occasions a Crayola crayon, a speckled marble and a chipped, porcelain hare. Was it neighborhood children depositing tokens for others to find, or was it indeed Boo longing to connect with others? Not long after, the knot hole was cemented over, and in time, the tree died and toppled over, succumbing to a hard winter wind. And in the spring when the birds sang, deep inside me I longed to hear a mockingbird. In time I came to learn that a fellow lived there who had once been a promising architect or some such and had suffered a personal tragedy. It was said that his elderly father would visit and make needed repairs to the house, but I'm sure he's long gone. Today, the only sign of life is a small bucket placed near the curb on recycling day filled with discarded water, ginger ale and Makers Mark 46 bottles. A lesson that I have learned in life is never to judge someone unless you've managed to walk around in their skin for a time and see things from a different perspective. And as for Boo, I think of the redemption we all eventually find within ourselves by way of the kindness of strangers, those who we down deep thought would never care yet come to surprise us by kind, simple acts placed directly in knot holes or deeds and words that endear them in our hearts. Once on our own porch swing, its gentle motion giving us comfort long after sunset, Chris asked: How will I know that I'm grown and am a man? Esteem You'll know, son, I replied, when the cherub-faced little girls have stopped chasing you down the street and expect you to chase them. You'll know when your heart is broken once, and yet again, and that life goes on. You'll know when you have overwhelming obstacles placed before you and embrace them as challenges that test your mettle. And you'll know, too, son, when you say farewell to a loved one whose path you have shared and whose journey now leads in a different direction. And in the end, you'll know you're a man not by what you think of yourself, but by the esteem in which you are held by others. For that realization alone, Harper Lee and Atticus Finch, I thank you from the bottom of my heart. Albert J. Parisi, a former copy editor at The Record and Herald News, is a writer and the author of the stage play "On a Wing and a Prayer." He resides in Bergen County. |

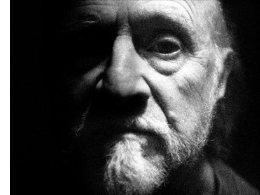

Richard Matheson: An AppreciationBy Albert J. ParisiTo generations, Matheson’s prose, through the genre of Fantasy and Science Fiction, touched countless readers because it explored, according to horror master Stephen King, “the depiction of one man locked in a desperate struggle against the force or forces larger than himself.” King credits Matheson as the one author “who influenced me the most as a writer.”  The same holds true for myself. He taught me about honest writing, life, and that in death, there is no end, just another beginning.

The same holds true for myself. He taught me about honest writing, life, and that in death, there is no end, just another beginning. I always knew that I wanted to write. Yet, as a high school freshman, when I first picked up a paperback copy of ‘I Am Legend,’ I knew all the more that I had to write and touch readers’ souls as Matheson had touched mine. In ‘Legend,’ published in 1954 and centering on the last surviving man in a world where a virus has turned the human race into vampires, Matheson explores the human condition of ultimate alienation and inner doubt born of tenuous insecurities. Which one of us has not known such alienation and doubt as a struggling teen in trying to make reason of the unforgiving world around us? In our own lives, the vampires were insensitive friends, overbearing parents, and in later years, bosses to which we must all answer and whose eyes are only on the bottom line. As a youth, I spent endless Sunday’s riding my Schwinn through an empty Bergen Mall in Paramus (thanks to the Blue Law in the days when it was still an open-air mall) imagining what it would be like to be the last person on Earth devoid of human contact. That sense of loneliness still haunts me. ‘Legend’ was filmed three times: As ‘The Last Man on Earth’ (1964) with Vincent Price, ‘The Omega Man’ (1971) with Charlton Heston, and most recently, as the acclaimed ‘I Am Legend’ with Will Smith in 2007. And yes, it was a trend-setter, the inspiration for George Romero’s cult-classic ‘Night of the Living Dead’ and decades later, ‘The Walking Dead,’ ‘28 Days Later’ and the newly released and much-hyped “World War Z” with Brad Pitt. As a journalist and in a 1994 New York Times Sunday feature, I had the honor of profiling the writer who had touched me so with his words. I recall him saying that the Romero film was but an homage to his novel in that “Homage means I can make the picture and I don’t have to pay you for your book.” In ‘The Shrinking Man,’ the protagonist, an everyday Joe, finds that his exposure to a radioactive mist causes him to gradually diminish in both size and stature in a frightening world that deeply explores alienation of friends, colleagues and loved ones. The protagonist becomes an outcast not by his own choosing in a society where “normal” is sacrosanct. As a social commentary written in 1956, the novel and film force us to embrace any and all who are challenged, or anyone who is different and unlike us because they, too, have the very same feelings, longings and dreams as we and must not be shunned.  He wanted to be remembered as on offbeat writer, but perhaps, he touched us most for his seminal work in Rod Serling’s ‘The Twilight Zone.’ Along with Serling and the late Charles Beaumont, Matheson penned such memorable episodes as ‘Nightmare at 20,000 Feet,’ with William Shatner as a neurotic air traveler who witnesses a gremlin on the wing of his plane intent on bringing it down; ‘Third From the Sun,’ in which a pair of scientists are intent on fleeing their world and saving their families from a fascist state by stealing a spacecraft and starting anew on a far-flung, fledgling and innocent planet called …Earth, and ‘Nick of Time,’ my personal favorite and also starring Shatner, in which a newlywed couple, with their lives before them, find refuge at a diner while their car needs repair only to fall under the influence of a coin-operated, bobble-headed devil of a fortune telling machine that preys on our superstitious protagonist’s sense of self-doubt. Obsessed with the all-knowing oracle, he is finally brought to his senses by his wife, who assures him the life they are about to embark on will be of their own choosing and that their love, dedication and devotion will see them through. He wanted to be remembered as on offbeat writer, but perhaps, he touched us most for his seminal work in Rod Serling’s ‘The Twilight Zone.’ Along with Serling and the late Charles Beaumont, Matheson penned such memorable episodes as ‘Nightmare at 20,000 Feet,’ with William Shatner as a neurotic air traveler who witnesses a gremlin on the wing of his plane intent on bringing it down; ‘Third From the Sun,’ in which a pair of scientists are intent on fleeing their world and saving their families from a fascist state by stealing a spacecraft and starting anew on a far-flung, fledgling and innocent planet called …Earth, and ‘Nick of Time,’ my personal favorite and also starring Shatner, in which a newlywed couple, with their lives before them, find refuge at a diner while their car needs repair only to fall under the influence of a coin-operated, bobble-headed devil of a fortune telling machine that preys on our superstitious protagonist’s sense of self-doubt. Obsessed with the all-knowing oracle, he is finally brought to his senses by his wife, who assures him the life they are about to embark on will be of their own choosing and that their love, dedication and devotion will see them through. Which of us can say that we’ve never known such self-doubt and that our own futures, at times, have seemed to hinge on little more than mere fate? That love conquers all was also a key theme in Matheson’s fiction and vision. As was the afterlife and reincarnation. In Matheson’s 1978 novel, ‘What Dreams May Come,’ the protagonist, a devoted family man and husband, is killed in a tragic accident. His ghost tries to re-assure his grieving wife that there is life after death and someday they will be reunited but she cannot hear him. Overwhelmed by her grief, she takes her own life and descends into a nightmarish netherworld of hopelessness where there is no rescue. Against all odds and, as Matheson writes, the laws of the universe, he takes on both heaven and hell to reach her and reclaim her tortured soul. Richard said to me that the novel, made into a 1998 film starring Robin Williams, was an extended love letter to his wife, Ruth Ann. “I don’t think of life after death,” he said during our long-ago interview. “To me, life after death and reincarnation are just slices of the pie. Life is a huge wheel and it goes around and around, and life after death is just a segment of that. I think we keep coming back until we learn what we need to learn, until we get it right. That which you think becomes your world, and it’s only when we’re alive and in this world that we have a chance to progress.” Thank you, Richard, for teaching myself and countless others that life is what we make of it, that death is not an end, and that there are no such things as obstacles, only challenges that enrich us, not drag us down. So here’s to the next life and know that your legend is your legacy to us all. Albert J. Parisi, of Wyckoff and a former copy editor at The Record/Herald News, is an award-winning journalist and the author of ‘On a Wing and a Prayer.’ He is currently working on a novel inspired by Matheson. |

Dead-on approach to classic literature scaryBy Albert J. ParisiAll writers down deep are particularly insecure and worried to death about the legacy they leave behind. I am certainly no exception. Ernest Hemingway, F. Scott Fitzgerald, Thomas Wolfe, Norman Mailer, no worries there. They made their name on the backs of sound and compelling books, but what were considered popular fiction in their day is not what sells today. It’s just not what the reading and viewing public is eating up.  Classic literature has nurtured generations, and when Hollywood gets involved, a new spin on an age-old tale seems like money in the bank. Classic literature has nurtured generations, and when Hollywood gets involved, a new spin on an age-old tale seems like money in the bank. I found myself surprised, bewildered and bemused on the latest movie version of Jane Austin’s “Pride and Prejudice.” This one is a period piece, of course, but “Pride and Prejudice and Zombies” offers a classic love triangle with a zombie apocalypse background, and our love-struck Victorian heroines are expertly trained ninja warriors, as easily adept at handling a sword as they are a delicate, porcelain tea cup. Tell me, is Jane Austin spinning in her grave? (Sorry, couldn’t resist that.) Or if she were with us today, would she wear a sly smile while watching her e-bank account grow since she would have negotiated a piece of the merchandising rights? The movie has garnered outstanding reviews. Heck, even Richard Roeper gave it three stars. I think he may have even called it bloody good. So here I am, a retired journalist in the midst of writing my first novel, tearing out my hair in constructing plot lines and developing memorable characters for a murder mystery set in WWII-Manhattan just after V.J. day, and fighting off the feeling that perhaps my time would be better spent pitching screen treatments of the classics, with a dead-on spin, of course. I had a haunting, fitful dream the other night. In it I’m meeting with my literary agent at his Manhattan office. Sample chapters in hand, I’m excited about my tale and detailing my progress. With his fingers pressed together against his chin and a thoughtful glance, he says: “Perhaps you should consider a back story to the main plot.” “Like what?” says I. “What about Nazi agents and missing gold?” “I could do that,” I reply. “Better still, how about zombies?” “Are you kidding me?” “No, zombies sell.” “Paul, you’re killing me, here. I think you’re dead wrong.” “Very funny, Al. Very funny.” Through the conference room door I see movement as a snarling and putrefied zombie comes crashing through the window, wrenching me from my seat in a shower of glass as it sinks its teeth into my throat, its cadaverous lips upon me. I wake up screaming to find my dog, Spunky, a mere Bischon, dancing on my chest, licking my face and telling me it’s time for his morning walk. Zombies, yeah, I could do zombies, at least for Hollywood’s sake. After all, Hemingway, Fitzgerald, even William Faulkner had cashed in on writing for the dream factory back in the day. And I have experience at being a zombie. At least I did when my son was born and I and my wife went with little or no sleep for months at a time during midnight feedings. But I had been forewarned. Decades before the popular AMC series had made its sanguine mark on countless viewers, a dear friend, a news anchor for a network affiliate out of New York, had said to me: “Welcome to the legion of the walking dead.” He and his wife had triplets the year before. But you couldn’t tell by him. Then again, he wore makeup on air. So, here are some thoughts on movies that would go over big, borne from classic literature: “A Farewell to Zombies”: In this memorable Hemingway tome, the setting is World War I and our hero, played by Johnny Depp, is an American volunteer ambulance driver gravely wounded on the front. Recuperating in a field hospital, he falls in love with his attending nurse, played by Keira Knightley. All around them, the wounded are dying … and coming back to life as, you may have surmised, zombies! The love of his young life becomes infected and our hero must now decide whether to do her in or join her for all eternity as a walking flesh eater. Classic Hollywood formula for success, kind of: Boy meets girl, boy losses girl, boy finds girl, both become zombies. Go figure. “The Great Gatsby and Zombie”: Fitzgerald’s classic story of love lost. Johnny Depp plays Jay Gatsby, (Leonardo DiCaprio, eat your heart out!) the zillionaire Long Islander longing to recapture his passion for Daisy, a lovely debutante from his past and portrayed by Salma Hayek. The problem is Daisy’s dead. As in zombie dead. Our hero learns that no amount of money in the world or well-connected politician’s promise can change that. Still, can true love overcome the ghoul-inducing virus? You just never know. “Charlie and the Zombie Factory”: With apologies to Roald Dahl, a remake of a remake starring Johnny Depp (Alright, so I’m a bit obsessed with Johnny Depp, but Variety just reported that he’s all aboard for yet another version of H.G. Wells’ “The Invisible Man.”) in which Willy Wonka must redeem himself and his eternal soul after years of running a factory that knowingly produces varieties of light and dark chocolates infused with the zombie virus and marketed to unruly teens and Grateful Dead fans. It’s not that I want to cash in on the trend, mind you. Not at all. I have my writer’s integrity and obligation to tell an entertaining story. Truth is, I’m most probably too late. I’ve got this nagging feeling that the above story lines have already been proposed and are in pre-production as we speak. Still, there’s always “The Naked and the Dead, The Musical.” Albert J. Parisi, of Wyckoff, is an award-winning writer and a former regional reporter for The New York Times. His novel is tentatively titled “Lost in the Shuffle” with an expected release date of early next year, that’s if the zombies don’t get to him first. |

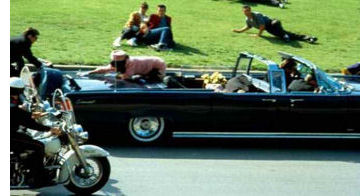

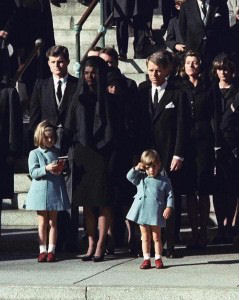

11/22/63: Innocence LostBy Albert J. ParisiOn that day so very long ago, I was a first-grader home from school with a cold. I recall that the air was crisp, the sky blue, with no indication of the dark cloud that was to befall us all, my family and the nation. My parents were Sicilian immigrants, my dad working a textile factory job in Paterson and my mom tasked with housework and raising a family. For them, the American Dream was a roof over our heads, food on the table and paying the bills. Yes, we were poor, but we just didn’t know it, compared to the abject poverty they had known in the “Old Country.” There was an old saying among immigrants, particularly those who had come through Ellis Island, as my parents had: “In America, the streets are not paved with gold, most streets are not paved at all and we are expected to pave them.” Hard work was the key to success, and my parents embraced that. In 1963, there was an air of hope, youth and vigor in what we all came to know as “Camelot.” My mom had a particular fondness for the Kennedys: Jackie was raising a young family, too, only in the White House. Jack had the weight of the world around his shoulders, as did any member of a struggling household, and mom and the president were the same age, both born in 1917.  Mom understood English but was not fluent. Still, that did not keep her from her favorite soap opera, “As the World Turns” on CBS. Mom understood English but was not fluent. Still, that did not keep her from her favorite soap opera, “As the World Turns” on CBS. On that day, lying in my pajamas before our small black and white television, we watched together the trials and tribulations of those soap opera characters whose lives were so very different from our own. As I recall, just after 2 p.m., the first bulletin hit: Three shots fired in Dallas. The President gravely wounded. In my memory, the images now are all a rapid blur with some etched in crystalline clarity over the course of four days that will last a lifetime: My mom’s face turning pale, a return to regular programing, an interruption again and Walter Cronkite, in tie, shirtsleeves and solemn, telling us of the developing tragedy. Tears streamed down my mother’s face and she choked back a sob as my voice gave credence to what she already knew: “The president’s been shot.” Another blur of faces and anxious voices and then, the image of Cronkite again, removing his glasses and glancing off-camera to a clock, confirming to a nation in a stoic voice on the verge of breaking that the president was dead.  I remember the shock and feeling of helplessness, but mostly I recall my mom bursting into tears, her shaking hands to her face and feet stomping the floor as her body was wracked by a spasm of unrelenting grief. We had lost a family member. I remember the shock and feeling of helplessness, but mostly I recall my mom bursting into tears, her shaking hands to her face and feet stomping the floor as her body was wracked by a spasm of unrelenting grief. We had lost a family member. At six, one’s parents are one’s world and sense of security and stability. For me, the fear that closed over my heart was more about seeing my mother stripped of that security than the death of a young president. In that very moment, for myself and a nation, our sense of innocence was lost. On that November day, my mother was inconsolable, and for the next four days, we grieved with the Kennedys and were captive to our TV. The arrival in Washington of the casket, the flag-draped caisson bearing the president’s body, a riderless horse following, and of John-John’s salute to his lost father as he was about to celebrate his own birthday. For me, that eternal flame in Arlington will always burn bright with hope, even at the cost of innocence. |

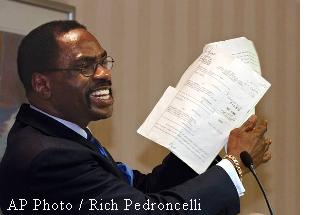

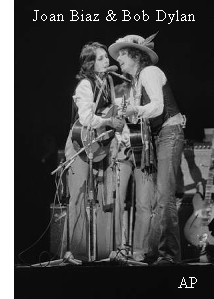

Opinion: The Season of the HurricaneApril 25, 2014, 4:07 PM — Last updated: Friday, April 25, 2014, 4:07 PMBy Albert J. ParisiTHE RECORDFor myself, part of that yardstick involved the murder retrial of Rubin “Hurricane” Carter back in 1976.  Carter, the embattled Paterson boxer known for his cold, withering stare and devastating left hook in the ring, beat a triple-murder charge after a decades-long fight when a U.S. District Court Judge overturned his conviction in 1985. Carter, the embattled Paterson boxer known for his cold, withering stare and devastating left hook in the ring, beat a triple-murder charge after a decades-long fight when a U.S. District Court Judge overturned his conviction in 1985.Carter died Easter Sunday at age 76 from complications of prostate cancer, yet his own resurrection began years ago in prison. As a 19-year-old college journalist, I covered that trial. I learned that dignity in the face of adversity can test a man’s mettle and that justice will always prevail, even if it takes years to make itself known. Folk singers Joan Baez and Bob Dylan performing before a crowd of about 20,000 people in New York City’s Madison Square Garden on Dec. 8, 1975, in a benefit concert for Carter. Carter, along with his happenstance partner, John Artis, went on to form Innocence International, a nonprofit group to help free prisoners it viewed as unjustly convicted, but the circus-like retrial will forever be with me.  Bob Dylan’s ode Bob Dylan’s ode In recent days when I’ve walked alone, I didn’t need an iPod to again hear the strains of a lonely fiddle and the gravelly voice of Bob Dylan: “Pistol shots ring out in a barroom night … Here comes the story of the Hurricane, the man authorities came to blame … put in a prison cell, but one time he could have been the champion of the world.” Those were some of the lyrics to Dylan’s “Hurricane,” his ode to Carter’s struggle released a month before the retrial. On the bandwagon, too, in the bid for exoneration were actors Warren Beatty, Ellen Burstyn and folk singer Joni Mitchell. Convicted murderers Carter and Artis, claiming innocence, were convicted murderers at the time. An all-white jury in 1966 found them guilty of slaying three whites in an aborted hold-up at the Lafayette Bar & Grill in Paterson. Yet new evidence, or the lack of it – including recanted pivotal testimony by one key witness – led to the retrial. I and a fellow journalism student, Chris Hartney from Dumont, attended the court proceedings at my insistence, armed with notebooks and a special photo-ID issued to “accredited journalists” by the Passaic County Sheriff’s Office. It was the first time I’d ever been fingerprinted. Cutting class and testing the patience of our journalism instructor, we received passing grades only after lecturing on our experiences. I remember the courtflies, as we called them, the curious and the odd who made the pilgrimage with us, standing in line for available courtroom seats. Among them were attorneys and the poor, like the aged black man in threadbare clothes who said he’s spent a lifetime knowing justice never to be served. He’d hoped to be a witness to change. When director Norman Jewison filmed “The Hurricane” in 1999, starring Denzel Washington as Carter, those were images that he failed to capture. Each morning, we’d gather at a coffee shop across from the courthouse, savoring the Bicentennial 76-cent special (greasy eggs, toast and coffee). It was an excuse to be privy to first-hand-information. Judge Bruno Leopizzi, charged with the trial, would speak of the previous day’s events off the record to reporters there. In the courtroom’s lobby, attendees were absorbed in a constant murmur: Would this be the day that rumors proved right, that Bob Dylan would make an appearance to show his support? Dylan never came, nor did Beatty nor the dozen or so other celebrities who had voiced indignation. Depth of the struggle For many of us, it was hard to imagine the depth of Carter’s struggle, let alone comprehend his endurance. In a brief hallway interview during a break in the retrial, I asked him to put it into words. He cocked his head at me like a fighter warding off a glancing blow and smiled, forgiving me my youthful lack of worldly experience. “You know, they can incarcerate and isolate my body for as long as they want, but never, ever my mind or my soul,” he said. In the courtroom each day, a stalwart guard would shake awake a disheveled older man in an ill-fitting sports jacket and stained tie, explaining that sleeping in court was not permitted. The character was the famed American novelist Nelson Algren, author of “The Man with the Golden Arm” and “A Walk on the Wild Side” who had left his beloved Chicago to prepare a grim, non-fiction book on Carter and his plight. He had taken an apartment in a seedy section of Paterson, but when a Sunday Record feature story profiled his intentions, Algren’s Hispanic landlord promptly showed him the door, labeling both him and the trial as “trouble.” Algren, whom Ernest Hemingway had called the greatest living American writer next to William Faulkner, saw his book as another shot at the literary title, yet following the retrial, no publisher would touch the book. Undaunted, this legend of letters turned it into a novel, “The Devil’s Stocking,” his last. It was published years later, a year after his death. He never received a penny from the book nor did it garner much-deserved recognition. Algren and I had become friends and neighbors: He had taken an apartment in Hackensack not far from me and when in a spot, I provided him a ride to and from the courthouse. Together, we visited Lou Duva’s boxing gym in downtown Paterson, where Carter had once trained. Duva admired Algren’s work and introduced the aging writer to his young, sweat-streaked students as “The Champ.” Nelson was kind enough to critique my early writings and provide me with encouragement and advice as a writer, all over cold Buds at his temporary home. He often regaled me with countless stories of his literary adventures. In time he would relocate to the northern tip of Long Island, Scott Fitzgerald country, as he called it. He died not long after, in near obscurity and with no family to speak of. When he was laid to rest there, they even spelled his name wrong on his tombstone. Recanting testimony And there were other characters: Alfred Bello, recanting his testimony, resembled a roly-poly Lou Costello with a darker side. Bello swore that as the finger man placing Carter and Artis at the scene of the crime, his testimony was coerced by police, wanting an easy solution to the case. Bello also admitted to walking into the bar that night, stepping over the dead and dying, and rifling through the cash register. Chris and I faced our own dangers. Paterson was still a racially divided city and the retrial brought back bad memories and opened many an old wound. As youthful and impetuous reporters, he and I decided to visit the original crime scene. I recall that with one hand on the bad end of a pool cue, a dour bartender explained that the bullet holes had long since been patched, that the blood stains were cleaned and that reporters were not welcome. We left in a hurry. The bar on the corner of Lafayette and 18th Street is still there, now home to Moya E. Bar-Liquors. From news reports, I gather that few in the neighborhood are aware of or care of Carter and his legacy. I remember during the trial and long afterwards a haunting voice, that of the narrator from the popular 1960s television series, “The Fugitive.” “Richard Kimble … tried and convicted for the murder of his wife. But laws are made by men, carried out by men. And men are imperfect.” The one-armed man Kimble, portrayed by David Janssen, had witnessed a one-armed man fleeing his home before discovering his wife’s lifeless body. I thought Carter, like Kimble, pondered his fate and saw only darkness. Then he dared to challenge authority and fight for his innocence. “But in that darkness, fate moves its huge hand.” For Rubin Carter and John Artis, there was no one-armed man to pursue and justice took its sweet time. Yet in the end, life’s final round, Rubin Carter fulfilled his destiny and championed the unjustly convicted of the world. Albert J. Parisi, a former copy editor at The Record and Herald News, is an award-winning journalist and the author of “On a Wing and a Prayer.” An online collection of short stories, entitled “Baby Boy and Other Tales of the Disenchanted,” is due for release this summer. He lives in Wyckoff. |

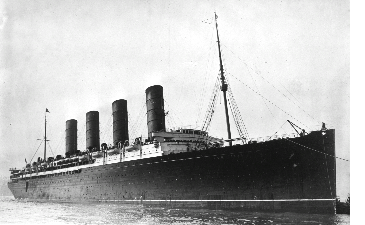

First Place Award, Columns 2016, Garden State Press AssociationOpinion: A delayed sailing, the Lusitania and the hand of fateMay 10, 2015 Last updated: Sunday, May 10, 2015, 1:21 AMBy Albert J. ParisiTHE RECORDLAST THURSDAY, I was reminded of an anniversary that I celebrate, although not always a conscious one. It is a day in which fate came to be the hunter, and my family's future was spared. Everything that I hold dear in life, my wife, son, joys and sorrows and life accomplishments, hinged on a single moment in history a century ago. Is it destiny on which our lives so precariously balance? The Record's Page One piece, "A prelude to war," gave me reason to ponder the question. My father, Albert, was a 14-year-old Sicilian immigrant who landed at Ellis Island together with his mother and 3-year-old brother on May 15, 1915. Together with memories of being processed and reunited with his father, Giovanni, a stone mason laboring to build the Bergen County Courthouse in Hackensack, Dad always had a tale to tell about their harrowing ocean crossing.  They traveled third-class steerage in the hold of an Italian steamer to escape poverty and embrace a new land with the promise of a better life. Delayed by two hours in their last port of call, their ship finally sailed and after rounding the southern coast of Ireland, set course for New York. They traveled third-class steerage in the hold of an Italian steamer to escape poverty and embrace a new land with the promise of a better life. Delayed by two hours in their last port of call, their ship finally sailed and after rounding the southern coast of Ireland, set course for New York. As was the custom then at sea, they crossed paths with a majestic ocean liner bound for England, a mere quarter mile separating both vessels as passengers crowded their decks waving and cheering, wishing each other well amid the wail of ships' horns. It was a sight, he would say, that he would never forget, long after the liner passed over the horizon. Warning Within hours, he recalled, the British cruiser (the HMS Juno) pulled alongside my father's steamer, ordering all aboard to don their life jackets because the liner they had just passed had been torpedoed by a German U-Boat. The liner was the Lusitania, and when she disappeared below the waves, she took with her 1,198 lives. Scores of those lost were U.S. citizens, 60 from New Jersey alone, and the incident would prompt America's entry in World War I just two years later. Had my father's steamer left port without being delayed, it would have been their ship in the crosshairs of a U-Boat commander's periscope sight. But I knew none of this growing up. As a senior in high school, decades before such information was a click away on the Internet, my curiosity one day drove me to the library and rolls of microfilm and a view screen. The New York Times for the month of May 1915 flashed before me. Scrolling to May 15, the day my father landed in New York, I saw nothing of the tragedy. I thought perhaps he'd gotten his dates wrong. Decades of memories have a way of blurring life's events, I reasoned. I scrolled forward a week. Nothing. I went back a week. Still nothing, and my frustration grew. Feeling defeated, I rewound the film at quick speed for a return to the reference desk when an image caught my eye and I froze the frame: Page 1, May 8, 1915. Lusitania sunk, lives lost. The accompanying photo was a long view of the storied liner, smoke streaming from her stacks. I remember going home and embracing my father. The details of my journey to discovery didn't matter for the moment. A fulfilling life My father went on to lead a rich and fulfilling life, but we were anything but wealthy. He toiled in the Paterson silk mills for close to 40 years. He buried two wives claimed by cancer and raised four children, often doing without so that we could have plenty. He became an American citizen and was proud of the achievement, even though he had roughly the equivalent of a third-grade education. Too young to serve in World War I, he found himself too old to serve in World War II, but he did his part for the war effort like millions of others by working as a machinist and assembler in 12-hour shifts at the vast Curtiss-Wright plant in Wood-Ridge. There they churned out Wright Cyclone R-3350 18-cylinder, air-cooled engines that were mated to the Boeing B-29 Superfortress bomber. All of those complicated engines originated in Wood-Ridge, and they carried a design flaw. The manifolds contained an element of magnesium and were known to burst into flames if run too hot. Dad recalled that they were tested on platforms in a parking lot far from the plant, with a technician armed with a fire extinguisher positioned about every fourth engine. I learned that the Lusitania was not to be my father's only tie to both history and destiny. In the 1980s as a young reporter for The New York Times, I was invited to the Smithsonian Air & Space Museum's Garber storage facility in Virginia to witness the restoration of the B-29 Enola Gay. The work was meticulous and I recall sitting in the pilot's left-hand seat where Col. Paul Tibbets had guided that aircraft over Hiroshima on Aug. 6, 1945. I remember, too, standing in the bomb bay where history took a fateful turn with just the flip of a simple switch releasing an atomic bomb. And most importantly, I recall a walk-around of the aircraft and running my hand along the nacelle of the No. 2 inboard engine and realizing that my father literally had a hand in building that engine that took that aircraft over Hiroshima that day to help bring a brutal and costly war to a close. Personal sacrifice On those days when I visit my father's grave, I'm reminded of his personal sacrifices and the life lessons that he passed on to his children: Stand up for what you believe, always follow your heart even though it can and will be broken, respect is born of honesty and integrity and in terms of work, do what you have to do until you can work at what you want to do. And each time I weigh my accomplishments and failures, embrace my wife and gaze into my son's eyes, I say two silent prayers, one in my father's memory and another for whatever power was responsible for a nondescript steamer's two-hour delay in port a century ago. Albert J. Parisi of Wyckoff, a former copy editor at The Record/Herald News, is an award-winning journalist and the author of "On a Wing and a Prayer." |

Opinion: Remembering our veteransNovember 11, 2015 Last updated: Wednesday, November 11, 2015, 1:21 AMBy Albert J. ParisiTHE RECORDON THIS DAY, Veterans Day, I'm reminded of General Douglas MacArthur's farewell speech to Congress in 1951 and his quote of an age-old ballad: "Old soldiers never die; they just fade away …" While they may fade from our memories, we as a nation must never forget their sacrifices or their cherished legacies. Especially those of our local veterans. I'm reminded nearly each day that many of us take for granted those freedoms for which they fought and which they helped preserve. As a writer and retired journalist, the right of free speech is what I choose to hold most dear.  In the 10-part Amazon-produced series "The Man in the High Castle," set for release this week and based on the "alternate reality" novel by Philip K. Dick, the United States is a conquered nation. The Germans are first to develop the atomic bomb and use it strategically. America is divided into two zones of occupation after a secession of hostilities, with the Mississippi River serving as the dividing line: Japan rules the west and Germany the east. In this world of domination and lingering rage, there is no freedom of the press, only a ruthless and intrusive ministry of propaganda. In the 10-part Amazon-produced series "The Man in the High Castle," set for release this week and based on the "alternate reality" novel by Philip K. Dick, the United States is a conquered nation. The Germans are first to develop the atomic bomb and use it strategically. America is divided into two zones of occupation after a secession of hostilities, with the Mississippi River serving as the dividing line: Japan rules the west and Germany the east. In this world of domination and lingering rage, there is no freedom of the press, only a ruthless and intrusive ministry of propaganda. As a young reporter, I'll always remember the comment of a Soviet journalist sitting across from me at a Frankfurt hotel bar in the early 1980s while I was on overseas assignment for The New York Times. The Berlin Wall had yet to fall, and we were discussing a hot-button topic. He raised his glass, looked me square in the eye and said this: "You Americans write about anything you please without impunity. In my country, if we write on painful issues, it is not we who disappear, but our families. You need to thank your lucky stars, or at the very least the headstones of your fallen still interred near the beaches of Normandy." And those cherished sacrifices and legacies of our local veterans run far and wide. In Raritan, Marine Sgt. John Basilone's ultimate sacrifice is recalled in a moving parade and tribute each September in his hometown. During World War II, he fought valiantly in the Pacific during the battle for Guadalcanal. He was the recipient of the Medal of Honor for his heroism, and with medal in hand, he returned home, took part in a war bond drive, and then chose to rejoin his comrades still in action. He was killed in February 1945 in the battle for Iwo Jima and was posthumously awarded the Navy Cross, the nation's second-highest honor. The parade (2016 will be its 35th year) grows annually, according to its organizers. Ridgewood's fighter ace By contrast, in Ridgewood, hometown of Thomas B. McGuire Jr. — the second-leading World War II fighter ace, with 38 confirmed victories — there is no annual parade or plan for one. Killed in action in early 1945 and also a Medal of Honor recipient, he is all but forgotten with the exception of his name etched into a war memorial at Van Neste Square. Due to the efforts of the Army Air Forces Historical Association, a non-profit, interactive living history museum based in Oradell, and one member in particular, Ridgewood resident Kevin Casey, whose father survived 25 missions flying over Fortress Europe in a B-17 bomber, there is now a permanent memorial to McGuire in the Knights of Columbus council hall downtown. McGuire Air Force Base in Wrightstown, formerly Fort Dix Army Air Base, was named in his honor in 1949. I think of three local WWII veterans whom we lost this year alone who, to a man, never viewed themselves as heroes. Each one would say he was only doing his jobs as a soldier and that the true heroes were those who never came home. Their sentiments are echoed today by those who fought and served in Iraq and Afghanistan. Herb Gold, 95, of Cresskill, a retired electrical worker, was a young gunner on a B-24 Liberator bomber when he was shot down over Germany in February 1945, on his 30th mission. He was taken prisoner and held in StalagLuft IV with thousands of other downed airmen. With the Soviet advance on the western front, the camp, along with a dozen other such camps, was ordered evacuated, with POWs used as negotiating pawns by the Germans. Forced march In one of the most brutal winters of the century, the POWs were told that they would take part in a three-day forced march. Three days became 80 days in sub-zero weather covering some 600 miles in what came to be known as "The Shoeleather Express." Countless POWs perished along the route; their numbers will never be known. Gold was one of the fortunate ones. Thoughts of his family, he would say, made him determined to survive. Ken Glemby, 92, of Woodcliff Lake was a replacement fighter pilot when he shipped overseas after D-Day. Flying a P-47 Thunderbolt, he was assigned to a remote airfield in France. As Christmas neared in December 1944, the Germans launched a surprise attack through the Ardennes Forest, laying siege on the U.S.-held crossroads town of Bastogne in what would come to be known as the Battle of the Bulge. Foul weather prevented relief for the encircled troops, but when the clouds finally lifted, Glemby and his squadron mates were first over Bastogne, relentlessly strafing German columns moving to capture the Belgian town. Glemby would say he remained forever haunted by the sight of such carnage. German troops late in the war, he explained, were nothing more than young boys and old men pressed into service. Glemby and his wife, Paula, would later open a successful insurance agency in Westwood. Rutherford native Calvin Spann, 90, would say that during the war years, he faced two common enemies: The Germans and racism. A P-51 fighter pilot and member of the Tuskegee Airmen, the segregated yet distinguished group of black Army Air Force fliers and ground-crew members, he was part of a two-man element that in combat shot down one of the first operational German fighter jets, known as the Me-262. Yet his own war, he would recall, began before his arrival for flight training in Alabama. Seated alone in a Pullman dining car heading south and departing Washington, D.C., he recalled a black train porter pulling down the shades around him. Asked the reason for such action, he was told matter-of-factly: "Son, I just saved your life. We're bound for the deep South, and I don't want some shine-soaked redneck taking a pot shot at you through that window." Spann would retire as a sales executive for a New Jersey-based pharmaceutical firm. Raising the flag I think of these veterans and thousands like them, those who came before them and those who will follow, and as I raise an American flag on my front porch today, Nov. 11, I'll think of one other veteran who invariably mans a table for the American Legion outside my neighborhood supermarket. For a donation of a dollar or two, he hands out with a grateful smile a blue cloth flower borne on a wire twist. I once asked what kind of flower it was. "Oh, these," he replied. "They're just forget-me-nots." Albert J. Parisi of Wyckoff, a former copy editor at The Record and Herald News, is an award-winning writer and the author of the stage play "On a Wing and a Prayer." |

Memories of an Inaugural Dance

|

For me, the experience will always remain bittersweet.

For me, the experience will always remain bittersweet.  What I recall most that day was the security. Everyone and anyone who could fit into a uniform seemed to have been drafted for the task, even when it came to inaugural balls.

What I recall most that day was the security. Everyone and anyone who could fit into a uniform seemed to have been drafted for the task, even when it came to inaugural balls.